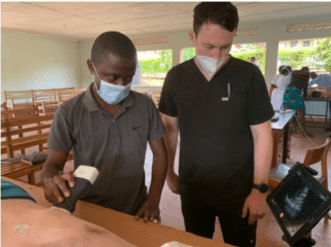

Third Year EM Resident Connor Schweitzer on his time in Blantyre…

It was amazing how often we heard those words during our trip. Stunning landscapes?

Welcome to Malawi. Luggage get lost? Welcome to Malawi. Medical license approval delayed?

Welcome to Malawi. Those words would play on repeat for 4 weeks, a refrain for everything I

experienced during my first global health trip to Africa.

As happens on big international trips, we didn’t have the smoothest start to our journey. A long delay in Ethiopia due to weather, bags that didn’t make it all the way to Blantyre, and far too little sleep left us thrilled to finally be on the ground. Having never been to Sub-Saharan Africa before, I wasn’t sure exactly what to expect. Driving from the airport to our home for the next month, I was struck by how green everything was. Hilltops covered with lush forest blanket the landscape during the rainy season. Farther on, we were treated to the bustling city of Blantyre and learned about the city, local mountaintops, and culture from the man driving, Zack Brady.

Zack and Carly Brady have lived and worked in Blantyre for the last 5 years after Carly completed her EM residency and Global Health fellowship in Columbia, SC. She took a job in the emergency department (AETC) at Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Queen’s) in Blantyre. Carly helped start the country’s first EM residency program. As people go, they don’t get much better than the Brady’s and their kids. They’ve built an incredible community in Blantyre and graciously helped us with every aspect of our rotation.

Without too much delay, we toured the Queen’s AETC. I was equal parts excited and apprehensive. However, upon entering the AETC for the first time, I recognized the familiar rhythm of the emergency department and felt more at home.

About a week and a few days later, I was working my first non-buddy shift in their high acuity zone (Resuscitation). At 07:30 AM, I took sign out on 5 acutely ill patients and proceeded to put my head down to take care of many new and existing patients. Thank goodness the nurses were experienced and helped me interpret for patients, order labs, dose medications (I was surprised at the amount of my dosing knowledge that is from an EMR), and overall keep everyone stable and alive. We succeeded as a team, and it was a great shift. After what felt like a little over a day’s worth of work and with 9 active patients under my care, I looked at the clock and noted the time.

It was 11:00 AM. Welcome to Malawi.

I had come to Malawi to be challenged, to learn, to improve my skills, to work hard, to broaden my outlook on medicine, and to hopefully help some folks along the way. After a few chuckles and some introspection, it became apparent I was getting exactly what I asked for.

The next couple of weeks went by in a flash. Each shift brought new opportunities to learn and grow as I treated diseases we rarely see in the US such as malaria, TB, bacterial meningitis, organophosphate poisonings, and more. Equally, I spent time learning from the nurses, interns, registrars (residents), and consultants (attendings), about how to practice medicine I thought I knew well in a different way.

Each shift brought new challenges and more than a few obstacles. By the last week, it felt like I was functioning as a real part of the Queen’s AETC team. We had built rapport with much of the staff. I had several significant emergencies while the sole doctor in Resuscitation that ran smoothly thanks to the amazing staff. Then suddenly, we were at the end. We celebrated with the people we had met from the AETC, had a wonderful last day of fun with the Brady’s, and our month in Malawi was over.

Global Health work can be complicated. You want to fill a need for people without infringing upon their established structures and cultures. Hopefully, you use your time and skills productively without imposing upon them. Ultimately, you’d like to collaborate, build community, and leave something that lasts and makes their lives genuinely better.

My time in Malawi felt exactly like a global health experience that produces the kind of lasting, profound change that these types of experiences should strive for. And it had nothing to do with me or the one month I spent there. Instead, it’s a product of the hard work from people like the EM Consultants in the Queen’s AETC, the global health faculty at Prisma, the EM registrars and staff at Queen’s, and many others whose partnerships, hard work, and tireless advocacy make the world and their communities a better place.

I can’t imagine a better experience to make me want to continue Global Health work in the future. Admittedly, I had begun to experience some burn out after nearly 7 years of medical school and residency training. Turns out, what I needed to lift my spirits was a Welcome to Malawi.

Then they asked for volunteers. One of my comrades bravely stepped forward and he was graciously received. They gently draped a grass skirt around his hips and began directing him in the most basic of movements. More and more volunteers added to the dancing mass until finally I could no longer resist the urge. My curiosity outweighed my fears of embarrassing myself and I stood up and allowed myself to be drawn into the madness. Rapidly we danced in circles and I focused intently on mimicking my partner’s moves exactly. In my mind it was like a scene from Footloose, Ugandan style.

Then they asked for volunteers. One of my comrades bravely stepped forward and he was graciously received. They gently draped a grass skirt around his hips and began directing him in the most basic of movements. More and more volunteers added to the dancing mass until finally I could no longer resist the urge. My curiosity outweighed my fears of embarrassing myself and I stood up and allowed myself to be drawn into the madness. Rapidly we danced in circles and I focused intently on mimicking my partner’s moves exactly. In my mind it was like a scene from Footloose, Ugandan style. surrounding these aid attempts needs to lie somewhere in the middle. While we must always strive to make our programs better we must also not allow ourselves to be incapacitated by the fear of failure. I am concerned that in a society where we are conditioned to measure quantitative data and measure success purely by objective calculations, we can find ourselves hesitating and missing opportunities as we pursue guaranteed success. If you want to dance, you must first step out onto the dance floor.

surrounding these aid attempts needs to lie somewhere in the middle. While we must always strive to make our programs better we must also not allow ourselves to be incapacitated by the fear of failure. I am concerned that in a society where we are conditioned to measure quantitative data and measure success purely by objective calculations, we can find ourselves hesitating and missing opportunities as we pursue guaranteed success. If you want to dance, you must first step out onto the dance floor. This scenario does not occur in the United States due to the 9.5 million individuals who donate blood in this country each year. Unfortunately, it is an all too common occurrence in many developing countries. According to the World Health Organization, only 40% of blood that is donated each year is collected in developing countries, however, these countries represent 80% of the world’s population. The situation is particularly dire in Sub-Saharan Africa where the HIV crisis makes suitable blood donors difficult to find. In addition, testing for many blood-borne infections that can be passed through transfusion are not available in many low-income countries, leaving those who do receive blood transfusions vulnerable to contracting HIV or Hepatitis.

This scenario does not occur in the United States due to the 9.5 million individuals who donate blood in this country each year. Unfortunately, it is an all too common occurrence in many developing countries. According to the World Health Organization, only 40% of blood that is donated each year is collected in developing countries, however, these countries represent 80% of the world’s population. The situation is particularly dire in Sub-Saharan Africa where the HIV crisis makes suitable blood donors difficult to find. In addition, testing for many blood-borne infections that can be passed through transfusion are not available in many low-income countries, leaving those who do receive blood transfusions vulnerable to contracting HIV or Hepatitis.